First, the backstory: At the turn of the century, I was one of many writers who maintained the odd beasts known as “online journals.” A few people back then were already using the word “blog,” but not many. I got to know people like John Scalzi and Pamela Ribon via their online journals way before they became well known for their other writing efforts.

I sometimes look at my journal’s archives just to remember what was going on in my life back then. Most of my old writing makes me cringe, but I’ll occasionally find a journal entry I consider halfway decent, and this is one of them. The two people I wrote about in this entry occupied quite a bit of my mental space at the time. If you’ve ever read my short story “MARA,” the character Scott is based on Mark, although I made Scott a drunk rather than a drug addict. (Then again, you probably haven’t read “MARA” unless you were at Borderlands Boot Camp in January or if you’re one of the many editors who’ve turned it down. But whatever.)

Here’s the original entry:

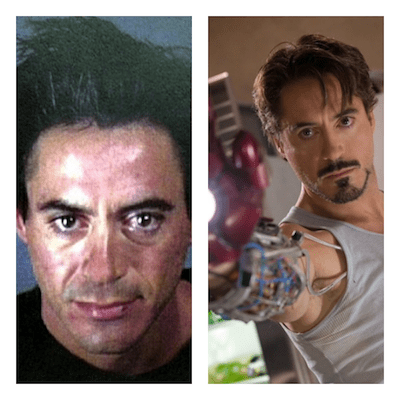

4/26/2001 — This Is Not About Robert Downey, Jr.

In the summer of 1993, I quit my first job without a net. A couple of my friends had landed long-term temp positions through a local agency, and I thought this sounded more appealing than my non-profit, non-advancement, non-respect, non-future job.

Who am I kidding? Ripping my nose hairs out with tweezers all day long sounded more appealing than my first job did by the time I left it. At the ripe old age of 24 I already felt stifled and stuck, millions of miles away from the editorial and literary stardom I’d always envisioned for myself.

After a summer of sparse temp assignments that left me so stony-ass broke that I actually felt relieved when my phone was disconnected because the bill collectors couldn’t hound me any more, I landed a temp-to-perm assignment at the national office of a union group over by Capitol Hill. That’s where I met Mark.

Mark and I had several things in common on the surface, and “on the surface” was good enough for me. We worked for the same temp agency, and we were both desperate to turn our positions with the union into permanent jobs. And we did. We had no choice. We had no insurance. We had no money.

But it turned out Mark had lost a lot more than I had. I learned in one of our early conversations that he’d gone from having a wife, a son, a great job, a house, and a flashy car to living in his parents’ basement. Alone. He’d lost his wife, custody of his son, and the rest of his American Dream.

Whoa. How the hell did that happen? I didn’t ask him directly, but I had to wonder.

Turns out Mark had a drug habit. He didn’t discuss it with me or with too many other people, but somehow almost everyone in the office knew it anyhow. I don’t know to this day what he used (the rumors were cocaine and heroin). I didn’t want to know much about it.

Mark struck me immediately as someone who could be a friend-and-maybe-more, and although he didn’t reciprocate the feeling he wanted me to think he did. I’ve noticed over the years that many people in the grip of addiction have an uncanny ability to read people and know who they can bullshit and exactly what they have to say to get what they want.

In my case, it was as if someone who knew me really well handed Mark a list of every button to push. “Tell her she’s really smart. Tell her how much cooler she is than the other girls who work here, and how glad you are to have someone you can really talk to. Tell her she’s sophisticated. Tell her she’s a hip city girl — she loves that. She hasn’t had a boyfriend in years. She’s lonely — flatter her, flirt with her a little, and she’ll be at your feet in a week.”

I didn’t have much to offer him besides cigarettes and the floor of my studio apartment as a place to sleep whenever he stayed out clubbing too late to catch the Metro. That got old fast, though. After three instances of Mark turning up at 2:30 in the morning and running his mouth until it was time for us to go to work, I learned to stop answering my phone after nine at night.

And sometimes — most of the time — he needed money. The guy would blow his entire paycheck the day he cashed it. He’d come back from the bank, tell me he was off to Georgetown to buy new Doc Martens, and return two hours later with no money left. I never loaned him large amounts because I just didn’t have it, but for a time I’d spot him a twenty. Hey, I was terrible with money too. Who was I to judge?

He wasn’t buying Doc Martens. He’d come back from the Georgetown trips completely agitated, glassy-eyed, jumpy, and unable to stay still for long. I never felt bold enough to bring up the drugs. Or maybe I did once and he just waved it off — it was something he did for kicks, but it wasn’t a problem.

But he started becoming really unreliable at work. He’d get in late. He’d go out for lunch and come back two hours later telling outlandish tales about major Metro wrecks that almost killed him. He’d take a bag of mail down to the mailroom in the lobby and be gone for an hour. Some days he just wouldn’t come in at all.

(He had me snowed so well that when his eventual replacement went to the mailroom and returned in two minutes, I was actually surprised. How fucking gullible can one person be?)

When our office manager confronted him about this, he’d cry. Mark could turn on the waterworks like a soap opera actress, and it freaked out the manager so much that she’d back off with a stammered request for him to try to do better.

I knew his job was in danger, I knew his parents were on the verge of tossing him out, and I knew he was fighting for visitation rights with his son and needed the money. At least once a day he’d come back to my desk to rant about someone — his mother, his ex, a lawyer.

I didn’t ever talk about drugs with him, but I would nag him about his shitty work habits. We’d sit in the lounge and he’d bum cigarettes from me and complain about the latest lecture from his manager. I’d try to be tough. He had to shape up, for his son’s sake if not his own, I’d say. Yes, the job was the pits, but he just couldn’t afford to lose it.

And of course the unspoken subtext in my pep talks was his drug habit. He understood that, too. He’d tell me he knew he needed to do better, and dammit, he was going to get his act together. The next day he’d roll in at 10:30 again.

I’m not sure just when I realized that Mark was a lost cause — if one single incident turned me off, or if I came to a gradual realization that Mark operated under a completely different behavioral code than I did, and I couldn’t affect something I couldn’t even begin to understand.

But it made me angry. I went from pulling for him to being completely disgusted with him. I got sick of his continued irresponsibility with his money and his job. I got tired of the way he blamed his screwups on everyone in his life except himself. I felt like I’d been had. I didn’t confront him outright; I simply withdrew from him.

And yet when he was finally fired from the job, long after he should have been, I cried. I left work that day to visit a friend of mine and ended up spilling the whole story. This friend had once been an addict, too, but he’d been clean for years — no drugs, no alcohol, no cigarettes. He told me about his own battle, and although I recognized something of Mark in my friend’s story, I couldn’t understand why my friend had been able to save himself, while Mark didn’t seem to want to get off his self-destructive path even as he knew it was costing him everything.

And I still don’t understand.

I watched this drama repeat itself a year after Mark left the company. Someone else in my life — someone who’ll go unidentified because it’s all just a little too close — landed in jail and then a rehab center because of her own drug addiction. And the treatments didn’t do a damn bit of good in the end. Time and again, she lands in the hospital or jail and swears that the experience scared her straight — she can’t live like this anymore and she’ll clean up for good.

Maybe she really does want to get better, or maybe she just knows all the right things to say to get people on her side. Maybe it’s both, but the addiction always wins out in the end. Our love and support make no difference. Our condemnation and anger don’t help, either. Something’s going on inside her that puts her beyond the reach of compassion or shame, rehab or jail. I don’t know why I tried pot a few times and never got hooked on anything else, while it started her on a long, tumultuous decline. And I just don’t know what it takes to turn someone back from that pit.

And I don’t know what happened to Mark. For a while, I’d bump into him in Dupont Circle or Adams-Morgan. But now that I don’t hang out in those places much anymore, I haven’t seen him in ages.

(For the record, I’ve never been a big Robert Downey, Jr. fan. The last thing I remember seeing him in was “Natural Born Killers.” I never found him any more talented than Nicolas Cage, Sean Penn, or a host of other actors rising up through the ranks at the same time he did. I’ll admit that he looked kind of cute and appealing in the Ally McBeal commercials I saw this year. But I’d rather let red ants eat my eyelids than watch Ally McBeal. And now it’s a moot point anyhow. It’s not like I’m losing sleep over what happened to him, but whenever he gets himself in the papers over another drug arrest, it kicks up all my memories of the people in my life with the same problem.)

#

Postscript, April 2019: I still have no idea what happened to Mark. I tried Googling him, but he shares a name with a semi-famous person, and all the hits I got were about that man.

The second person I wrote about died a few years ago. She’d been mentally gone long before her actual death, but her physical body finally gave out after the decades of substance abuse.

I still see my supportive friend around DC sometimes, and he’s still happy and healthy.

And of course Robert Downey, Jr. turned out OK after all. I posted this the weekend that “Avengers: Endgame” came out, and the movie’s on track to gross all the money in the world and he’s a huge part of why. I’m truly glad to see that, because back when I wrote the above, he was little more than a punchline for bad taste junkie jokes. And I do consider myself a fan of his now: I like him a lot as Iron Man, but also enjoyed him in films like Zodiac and A Scanner Darkly. Mostly, I’m really glad that he survived. Younger people might never know how questionable that seemed back in 2001.